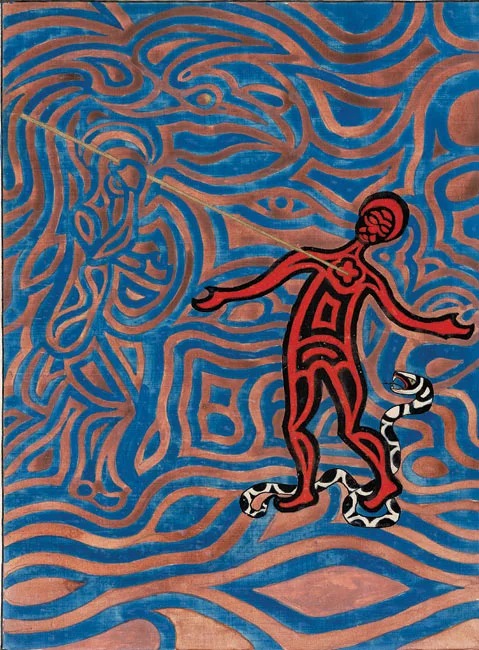

Carl Jung, The Red Book

Be silent and listen: have you recognized your madness and do you admit it? Have you noticed that all your foundations are completely mired in madness? Do you not want to recognize your madness and welcome it in a friendly manner? You wanted to accept everything. So accept madness too. Let the light of your madness shine, and it will suddenly dawn on you. Madness is not to be despised and not to be feared, but instead you should give it life...If you want to find paths, you should also not spurn madness, since it makes up such a great part of your nature...Be glad that you can recognize it, for you will thus avoid becoming its victim. Madness is a special form of the spirit and clings to all teachings and philosophies, but even more to daily life, since life itself is full of craziness and at bottom utterly illogical. Man strives toward reason only so that he can make rules for himself. Life itself has no rules. That is its mystery and its unknown law. What you call knowledge is an attempt to impose something comprehensible on life.

The history of early American anti foraging laws reveals that supporters of restricting foraging rights

typically grounded their efforts in racism, classism, colonialism, imperialism, or some combination of these odious practices and beliefs

Louis Lingg took his own life in a final act of defiance against The United States that sentenced him to death for the alleged throwing of a bomb at a workers rights protest. Happening on May 4th 1886 The Haymarket Affair is regarded as one of the most significant worker protests in US history and would lead to America establishing the 40 hour work week.

'Anarchy means no domination or authority of one man over another, yet you call that 'disorder.' A system which advocates no such 'order' as shall require the services of rogues and thieves to defend it you call 'disorder.' The Judge himself was forced to admit that the states attorney had not been able to connect me with the bombthrowing. The latter knows how to get around it, however. He charges me with being a 'conspirator.' How does he prove it? Simply by declaring the International Working Peoples Association to be a 'conspiracy.' I was a member of that body, so he has the charge securely fastened on me. Excellent! Nothing is too difficult for the genius of a states attorney!'

The universal misery, the ravages of the capitalistic hyena have brought us together in our agitation, not as persons, but as workers in the same cause. Such is the 'conspiracy' of which you have convicted me.

I tell you frankly and openly, I am for force. I have already told Captain Schaack, 'if they use cannons against us, we shall use dynamite against them.' I repeat that I am the enemy of the 'order' of today, and I repeat that, with all my powers, so long as breath remains in me, I shall combat it. I declare again, frankly and openly, that I am in favor of using force. You laugh! Perhaps you think, you will throw no more bombs' but let me assure you I die happy on the gallows, so confident am I that the hundreds and thousands to whom I have spoken will remember my words and when you shall have hanged us, then mark my words they will do the bombthrowing! In this hope do I say to you: I despise you. I despise your order, your laws, your force propped authority. Hang me for it!"

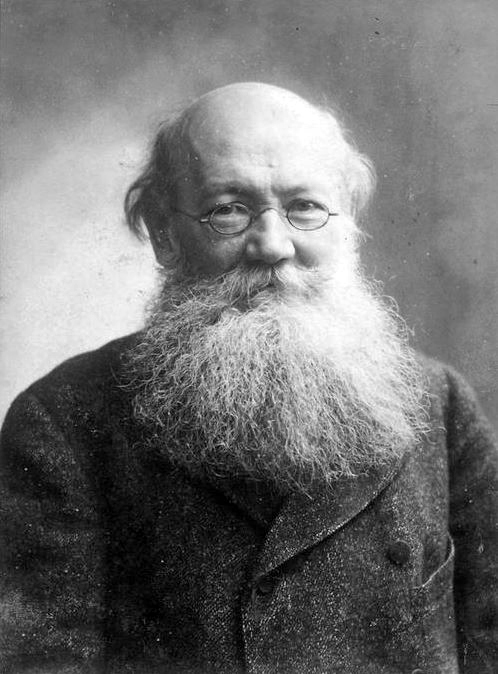

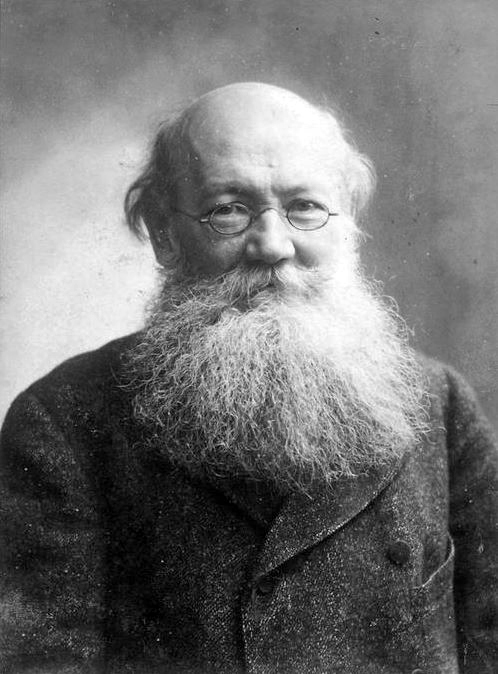

Pyotr Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread

In our civilized societies we are rich. Why then are the many poor? Why this painful drudgery for the masses? Why, even to the best paid workman, this uncertainty for the morrow, in the midst of all the wealth inherited from the past, and in spite of the powerful means of production, which could ensure comfort to all, in return for a few hours of daily toil?

The Socialists have said it and repeated it unwearyingly. Daily they reiterate it, demonstrating it by arguments taken from all the sciences. It is because all that is necessary for production, the land, the mines, the highways, machinery, food, shelter, education, knowledge, all have been seized by the few in the course of that long story of robbery, enforced migration and wars, of ignorance and oppression, which has been the life of the human race before it had learned to subdue the forces of Nature. It is because, taking advantage of alleged rights acquired in the past, these few appropriate to day two thirds of the products of human labour, and then squander them in the most stupid and shameful way. It is because, having reduced the masses to a point at which they have not the means of subsistence for a month, or even for a week in advance, the few can allow the many to work, only on the condition of themselves receiving the lion's share. It is because these few prevent the remainder of men from producing the things they need, and force them to produce, not the necessaries of life for all, but whatever offers the greatest profits to the monopolists. In this is the substance of all Socialism.

Take, indeed, a civilized country. The forests which once covered it have been cleared, the marshes drained, the climate improved. It has been made habitable. The soil, which bore formerly only a coarse vegetation, is covered to day with rich harvests. The rock walls in the valleys are laid out in terraces and covered with vines. The wild plants, which yielded nought but acrid berries, or uneatable roots, have been transformed by generations of culture into succulent vegetables or trees covered with delicious fruits. Thousands of highways and railroads furrow the earth, and pierce the mountains. The shriek of the engine is heard in the wild gorges of the Alps, the Caucasus, and the Himalayas. The rivers have been made navigable, the coasts, carefully surveyed, are easy of access artificial harbours, laboriously dug out and protected against the fury of the sea, afford shelter to the ships. Deep shafts have been sunk in the rocks, labyrinths of underground galleries have been dug out where coal may be raised or minerals extracted. At the crossings of the highways great cities have sprung up, and within their borders all the treasures of industry, science, and art have been accumulated.

Whole generations, that lived and died in misery, oppressed and ill treated by their masters, and worn out by toil, have handed on this immense inheritance to our century.

For thousands of years millions of men have laboured to clear the forests, to drain the marshes, and to open up highways by land and water. Every rood of soil we cultivate in Europe has been watered by the sweat of several races of men. Every acre has its story of enforced labour, of intolerable toil, of the people's sufferings. Every mile of railway, every yard of tunnel, has received its share of human blood.

The shafts of the mine still bear on their rocky walls the marks made by the pick of the workman who toiled to excavate them. The space between each prop in the underground galleries might be marked as a miner's grave, and who can tell what each of these graves has cost, in tears, in privations, in unspeakable wretchedness to the family who depended on the scanty wage of the worker cut off in his prime by fire-damp, rock-fall, or flood?

The cities, bound together by railroads and waterways, are organisms which have lived through centuries. Dig beneath them and you find, one above another, the foundations of streets, of houses, of theatres, of public buildings. Search into their history and you will see how the civilization of the town, its industry, its special characteristics, have slowly grown and ripened through the cooperation of generations of its inhabitants before it could become what it is to day. And even to day, the value of each dwelling, factory, and warehouse, which has been created by the accumulated labour of the millions of workers, now dead and buried, is only maintained by the very presence and labour of legions of the men who now inhabit that special corner of the globe. Each of the atoms composing what we call the Wealth of Nations owes its value to the fact that it is a part of the great whole. What would a London dockyard or a great Paris warehouse be if they were not situated in these great centres of international commerce? What would become of our mines, our factories, our workshops, and our railways, without the immense quantities of merchandise transported every day by sea and land?

Millions of human beings have laboured to create this civilization on which we pride ourselves to-day. Other millions, scattered through the globe, labour to maintain it. Without them nothing would be left in fifty years but ruins.

There is not even a thought, or an invention, which is not common property, born of the past and the present. Thousands of inventors, known and unknown, who have died in poverty, have cooperated in the invention of each of these machines which embody the genius of man.

Thousands of writers, of poets, of scholars, have laboured to increase knowledge, to dissipate error, and to create that atmosphere of scientific thought, without which the marvels of our century could never have appeared. And these thousands of philosophers, of poets, of scholars, of inventors, have themselves been supported by the labour of past centuries. They have been upheld and nourished through life, both physically and mentally, by legions of workers and craftsmen of all sorts. They have drawn their motive force from the environment.

The genius of a Seguin, a Mayer, a Grove, has certainly done more to launch industry in new directions than all the capitalists in the world. But men of genius are themselves the children of industry as well as of science. Not until thousands of steam engines had been working for years before all eyes, constantly transforming heat into dynamic force, and this force into sound, light, and electricity, could the insight of genius proclaim the mechanical origin and the unity of the physical forces. And if we, children of the nineteenth century, have at last grasped this idea, if we know now how to apply it, it is again because daily experience has prepared the way. The thinkers of the eighteenth century saw and declared it, but the idea remained undeveloped, because the eighteenth century had not grown up like ours, side by side with the steam engine. Imagine the decades that might have passed while we remained in ignorance of this law, which has revolutionized modern industry, had Watt not found at Soho skilled workmen to embody his ideas in metal, bringing all the parts of his engine to perfection, so that steam, pent in a complete mechanism, and rendered more docile than a horse, more manageable than water, became at last the very soul of modern industry.

Every machine has had the same history a long record of sleepless nights and of poverty, of disillusions and of joys, of partial improvements discovered by several generations of nameless workers, who have added to the original invention these little nothings, without which the most fertile idea would remain fruitless. More than that: every new invention is a synthesis, the resultant of innumerable inventions which have preceded it in the vast field of mechanics and industry.

Science and industry, knowledge and application, discovery and practical realization leading to new discoveries, cunning of brain and of hand, toil of mind and muscle—all work together. Each discovery, each advance, each increase in the sum of human riches, owes its being to the physical and mental travail of the past and the present.

By what right then can any one whatever appropriate the least morsel of this immense whole and say This is mine, not yours?

Farish Odeh

Faris Odeh (3 December 1985, 8 November 2000) was a Palestinian boy from the Israeli occupied Gaza Strip who became known as a popular symbol for Palestinian resistance because of a photograph where he is seen throwing a stone at an Israeli tank during the Second Intifada. In November 2000, he was killed by Israeli troops near the Karni Crossing while he was throwing stones at them.

A picture of Odeh standing alone in front of a tank, with a stone in his hand and arm bent back to throw it, was taken by a photojournalist from the American non-for-profit Associated Press on 29 October 2000. Ten days later, on 8 November, Odeh was again throwing stones at Karni when he was shot in the neck by an Israeli soldier. The boy and the image subsequently assumed iconic status within Palestinian movement as a symbol of their opposition to the Israeli occupation.